Published April 13, 2018

Two Key Considerations For Managing Xcode Configurations

What’s this about?

Most iOS (and macOS) developers have a love/hate relationship with Xcode. It seems the larger the

team, the more the emotions lean towards “hate.” There are a lot of reasons for this, but one we can

do something productive about is managing build settings. Enter xcconfig files.

Files with the extension xcconfig are used by the Xcode IDE to externalize build settings

usually edited within the Xcode GUI.

Why do I care?

Because these settings are almost never referenced, it’s not uncommon for a setting to be unintentionally modified by a co-worker. Common causes of this include search paths changing, a mistaken drag-and-drop operation, or somebody blindly following advice found on the internet.

Further (and more importantly, since your team is absolutely perfect, and never makes those mistakes) by externalizing settings, you gain several superpowers. It’s much easier to:

- Share configurations consistently across subprojects and/or targets

- Review configuration changes in git history

- See which of your settings diverge from the stock Apple settings

- Review changes before merging

- Layer settings to make a complex project more comprehensible

Tell me more!

Because Xcode has changed so much over the years, and because the way you create each of these things doesn’t reflect how they’re displayed, let’s take a quick crash course in terminology, so we’re all on the same page.

Workspace: A collection of one or more Projects, often used to simplify dependency management.

Project: The bundle on disk with the extension xcodeproj, representing your application’s

build rules.

Target: A specific “thing” being built by the Project, like an application, or a framework. A

single Project may contain multiple Targets.

Configuration: Sometimes referred to as “build style.” It’s frequently used to differentiate

between Debug and Release, or beta and deployment builds. Each Configuration is layered on top of

each Target.

Now, with that in mind, I think it’s easiest to think of project settings as two sets of layered

rules. One set is universal, regardless of which application you’re building. The other set is

very specific to the thing you’re building. Let’s call those UniversalSettings and TargetSpecificSettings. We build

both sets of settings from the least specific to the most specific.

UniversalSettings

The least specific build settings will be referred to as Common. These rules should include things

like which sets of warnings you use, or what version of the iOS SDK you’re targeting. These settings

are universal (regardless of Target or Configuration) and I typically store them in a file

called Common.xcconfig.

The more specific settings are the ones that differ between Configurations. For example, you might

build your application as either Debug or Release. The settings that change between Debug and

Release would include optimization level, preprocessor flags and conveniences like

ONLY_ACTIVE_ARCH (used to reduce build times). Continuing with our naming convention, I name

those two files Debug.xcconfig and Release.xccconfig. The first line of each of those files

begins with the following code to import the common settings.

#include "Common.xcconfig"

TargetSpecificSettings

The second set of rules I refer to as “per-target settings.” Here, you would set things that wouldn’t be shared across multiple applications, like bundle identifier, application name and so forth. (I’m using Application as the Target type, but all of these guidelines apply equally to frameworks, libraries, extensions, and so on).

The common file contains LIBRARY_SEARCH_PATHS to locate all the shared frameworks, and other

things that are 100% universal to the Target’s build process. These get placed in a file with a

slightly different name: MyApp-Common.xcconfig.

Why the different names? One reason is to help you mentally separate the universal stuff from the target

settings. A second is because Xcode gets very confused if a Project or Workspace references two or

more files with the same name. The resulting builds, if they work at all, are likely to not be

what you expected.

The Debug and Release Configurations might supply different bundle identifiers and display names,

allowing you to install both Release and Debug builds of your product on the same device,

simultaneously. Like the earlier set, each of the variant files imports the Common settings, but

with one little twist.

MyApp-Release.xcconfig

#include "MyApp-Common.xcconfig"

MyApp-Debug.xcconfig

#include "MyApp-Common.xcconfig"

#include? "Developer.xcconfig"

We’ll discuss Developer.xcconfig in a moment.

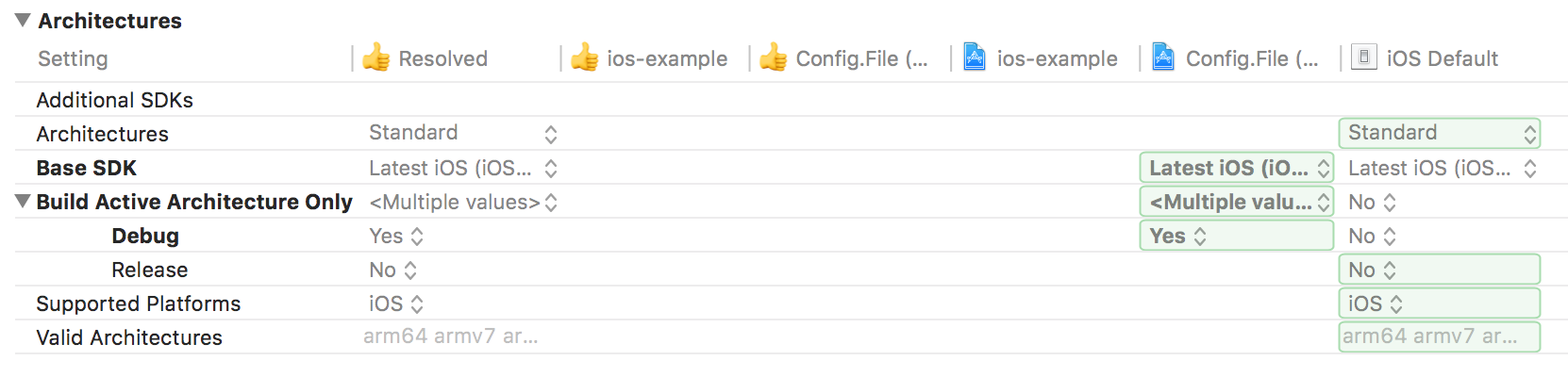

Once you have your settings files arranged, you probably want to know how to hook them up. Here’s Xcode, displaying the external configurations.

Things to note:

The display has two build configurations: Debug and Release.

When building Debug, the Project uses the Debug.xcconfig file (which we know imports

Common.xcconfig.)

When building the Target “myapp-ios-example,” the Target uses the

MyApp-Debug/Release.xcconfig file, which includes MyApp-Common.xcconfig.

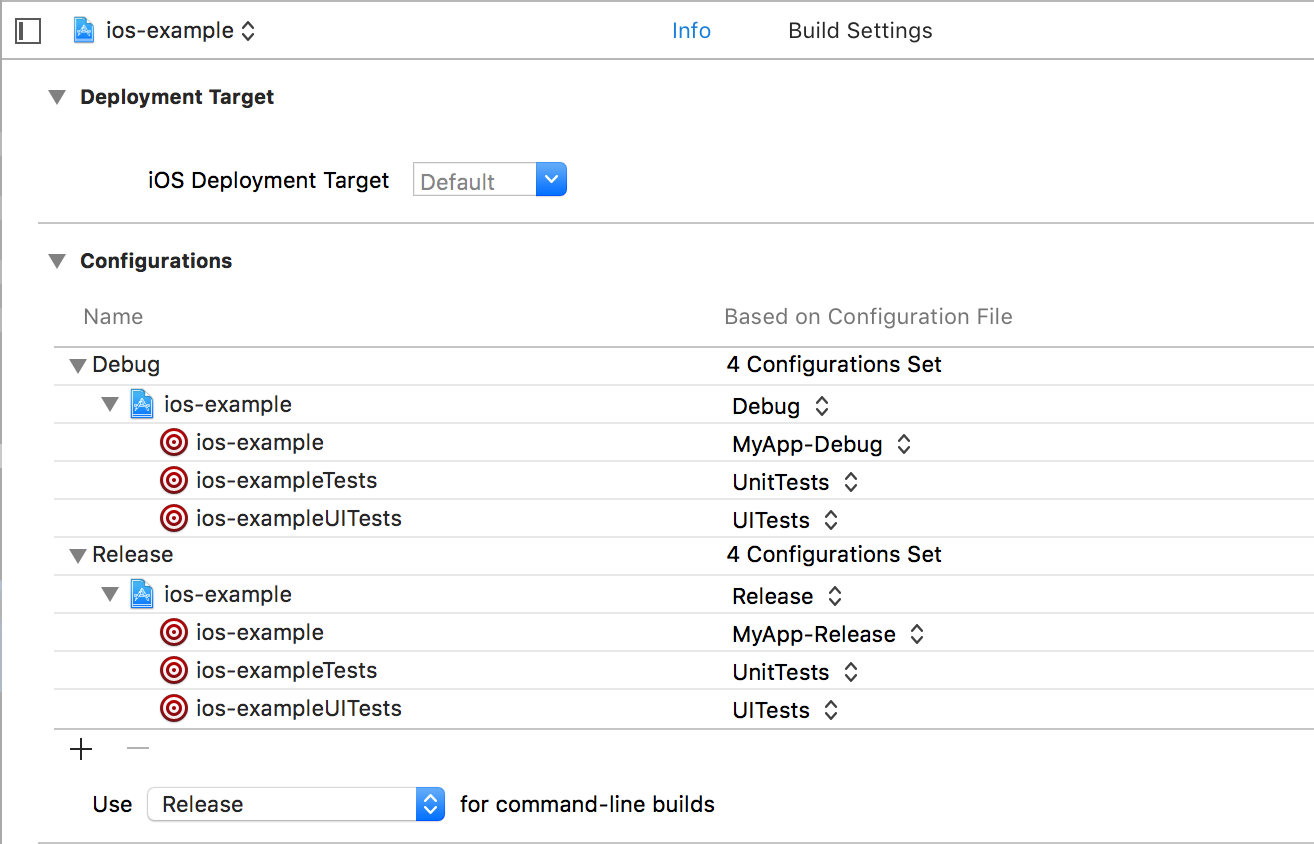

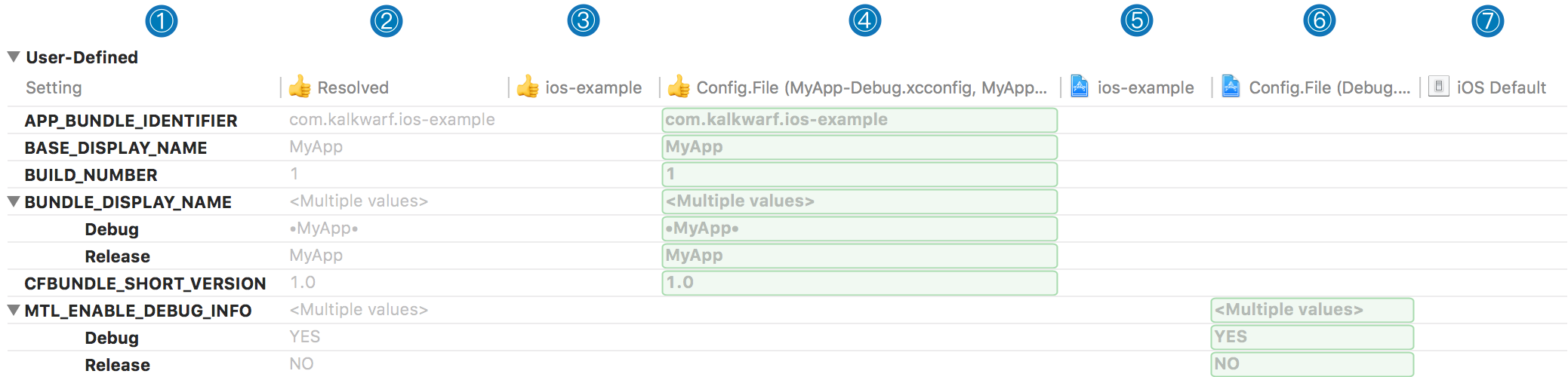

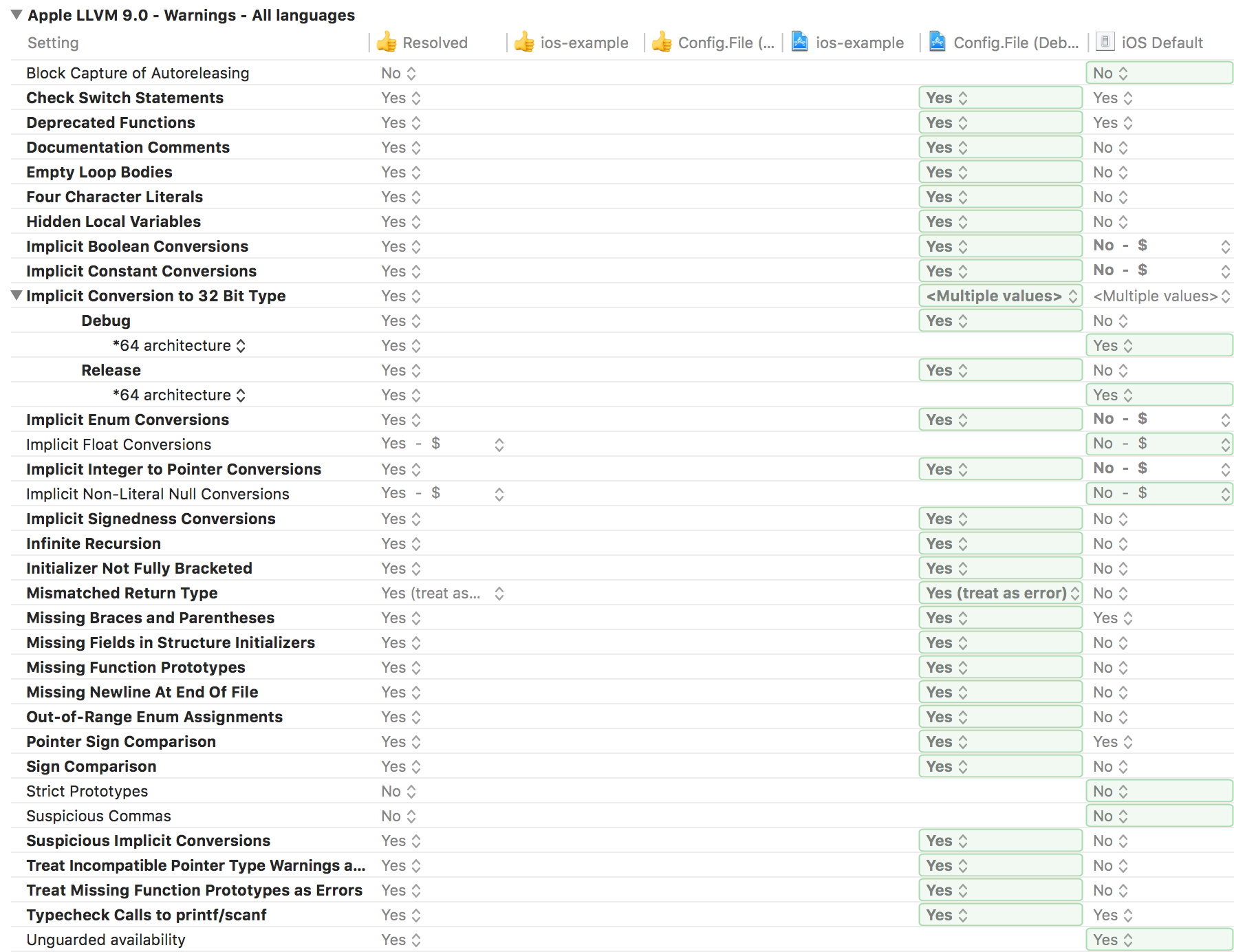

Here’s a screenshot showing a project file that has had its settings externalized in the way described above.

NOTES:

- Items drawn with bold text are changed from the iOS default.

- The final setting, calculated from right to left.

- Settings configured on the Target in the project file. Do not use these!

- Target-specific config file.

- Settings configured on the Project in the project file. Do not use these!

- Universal config file.

- Apple’s defaults.

Now that you’ve taken control of your settings, here are a couple of cool tips to take things to the next level.

ProTip #1: Optional includes

Possibly the best-kept secret about xcconfig files is you can have an optional import by using

the #include? directive. Remember Developer.xcconfig?

If you create and populate that file, in the same directory as MyApp-Debug.xcconfig, anything

in it will augment or override the settings gathered from the previously seen files. If you don’t

have that file present, no warnings or errors are generated, and life happily continues on its way.

ProTip #1a: An example

On my machine, Developer.xcconfig contains the following code to dynamically load the Reveal debugging tool.

OTHER_LDFLAGS = $(inherited) -weak_framework RevealServer

FRAMEWORK_SEARCH_PATHS = $(inherited) /Applications/Reveal.app/Contents/SharedSupport/iOS-Libraries

This isn’t in the shared config file, because not everyone on the team uses that tool, and populating those settings would cause build warnings or errors for those who do not.

Regardless of whether you have a Developer.xcconfig, if you provide support for it, be sure to

update your .gitignore, so it doesn’t get committed accidentally.

ProTip #2: XcodeWarnings.xcconfig

If you’ve looked closely at the Errors and Warnings section of Xcode’s settings, you’ll probably feel dread, contemplating migrating them all to your config. Fortunately, a kind soul has already done so, and made that xcconfig available on GitHub.

Include that from one of the other xcconfigs, and all the warnings available will be enabled. (I

include it from Common.xcconfig)

Conclusion

Xcode’s ability to use external configuration files is an underappreciated feature, which makes managing settings easier, and makes it possible to manage complex projects rationally.

Further reading

As mentioned previously, the documentation for these settings is a little sparse, but here are two older, but still accurate links to Apple’s documentation: